Avant l’heure c’est déjà l’heure, yen a qui font déjà leur lettre au Père Noël

FNSEA 4 février 2026

Cher petit Papa Noël, cher gouvernement de la Ripoublique, nous ne sommes qu’en février mais nous avons déjà de bonnes idées pour préparer Noël, ou avant si tu pouvais, Pâques, ou la Pentecôte, ou l’Ascension …

Tu trouveras ici une petite liste de petites gentilles courses qu’il nous plairait que tu fasses pour nous dans les plus brefs délais. ..

Loi d’urgence agricole

Propositions de mesures urgentes

Cette note reprend, en les accompagnant de propositions concrètes, les dispositions qui devront figurer dans la loi d’urgence. Ces dispositions seront proposées au gouvernement. Il conviendra toutefois de les prioriser, un tel projet de loi ne pouvant porter que des mesures à caractère urgent et en nombre nécessairement limité.

Exposé des motifs

-

Face au constat de décroissance qui frappe notre agriculture, illustrée par le déficit inédit de la balance commerciale agroalimentaire de la France en 2025, une relance de l’agriculture, un développement de notre souveraineté agricole et une lutte contre la décroissance sont plus que jamais nécessaires ;

-

Un changement de paradigme attendu qui doit aller jusqu’à des modifications de la Constitution (cf propositions à venir du RO de la FNSEA : proposer un principe d’innovation et garantir l’approvisionnement agricole dans la Constitution ;

-

De nombreuses réglementations doivent être revues : moyens de production, eau, prédation, sanitaire, bien-être animal, fiscalité, foncier, emploi, agro-énergie…

-

Un lien avec les prochaines lois de finances est indispensable sur de nombreuses questions : suppression de la RPD, exonération de TFNB de certains zonage environnementaux, suppression de la taxation des engrais en cas de non -atteinte des objectifs sur l’ammoniac et le protoxyde d’azote, exonération des logements des salariés…

-

Une priorisation dans les urgences est cependant nécessaire : il ne s’agit pas de refaire une loi d’orientation et le pas de temps politique limité ;

-

Ce qui ne nous interdit pas d’avoir un discours ambitieux et de le concrétiser dès maintenant de nombreuses mesures qui devront être complétées par d’autres textes qui devront voir le jour à l’issue des élections présidentielles ;

-

Les mesures proposées se décomposent en quatre chapitres :

-

Un chapitre « transversal » posant les règles de reconstitution de notre potentiel de production ;

-

Trois chapitres contenant les dispositions urgentes intéressant les trois thématiques annoncées par le Premier ministre.

-

Un préalable incontournable : Reconstituer nos capacités de production

-

Relancer et augmenter la production agricole en France

-

Inscrire un objectif ambitieux de reconquête d’une balance agroalimentaire positive :

-

Définir des objectifs chiffrés et des délais pour les atteindre pour chaque filière ;

-

Planifier les investissements nécessaires et les politiques d’accompagnement

-

-

Faciliter les projets pour atteindre les objectifs de souveraineté agricole fixés par les filières :

-

Décliner les plans de filières sur les territoires et définir les investissements prioritaires ;

-

Engager un accompagnement financier et fiscal de l’Etat, alléger les procédures…

-

-

Intégrer un principe de non-régression de la production agricole et de l’équilibre économique des exploitations dans les zonages environnementaux :

-

Tous les zonages doivent être concernés (aires d’alimentation de captages, zones humides, zones d’expansion de crues, zones Natura 2000, zones vulnérables, ZNT, parcs naturels pour la prédation…) : démontrer que l’on maintient la valeur ajoutée agricole ;

-

Revoir le principe du « ZAN » pour les projets agricoles.

-

-

-

Interdire toute surtransposition Europe / France / local

Eviter la surenchère normative nationale et locale en inscrivant, dans un nouvel article au Livre préliminaire du code rural, l’interdiction de surenchère normative nationale et locale par rapport au droit européen, sauf justification au regard d’un intérêt général

-

Accélérer les projets agricoles et limiter les recours

-

Encadrer les délais d’instruction des projets :

-

Obliger à instruire dans un délai total maximum ;

-

-

Limiter les possibilités de recours :

-

Compléter les dispositions prévues dans la LOSARGA (étendre le champ de la suppression d’un degré de juridiction à d’autres domaines…) ;

-

Poser un principe de « cristallisation du droit » : aucun recours ne peut avoir pour fondement un texte réglementaire postérieur au dépôt du dossier !

-

-

Créer un régime d’exception tant que les objectifs de souveraineté agricole ne sont pas atteints :

-

Simplifier les modalités d’instruction et limiter les recours pour tout projet prioritaire répondant à un déficit de production -identifié comme tel- eu égard au déficit de production national (régime temporaire tant que l’objectif n’est pas atteint) ;

-

Copier les régimes d’exception mis en place pour la reconstruction de Notre-Dame de Paris ou des JO d’hiver.

-

-

Eau

-

SDAGE / SAGE :

-

Systématiser les études socio-économiques concernant l’agriculture pour l’élaboration des SDAGE et SAGE

-

Obliger à une justification des mesures allant au-delà des cadres législatifs et réglementaires

-

-

Limiter les surfaces agricoles zonées en aires d’alimentation de captages, en zones humides et en zones vulnérables

-

Retirer la notion de captages sensibles dans la loi ?

-

Intégrer la définition des zones humides fonctionnelles

-

Retravailler les modalités de classement des zones vulnérables (législatif ?)

-

-

Poser un objectif quantitatif à atteindre en termes de stockage de l’eau et augmenter les volumes prélevables pour l’agriculture

-

Intégrer dans le code rural un objectif national d’augmentation des plans d’eau permanents ou non et le décliner dans les SDAGE

-

-

Faciliter l’entretien des cours d’eau

-

Poser un principe d’accord à défaut de réponse négative ?

-

Simplifier les entretiens au regard de la réglementation sur les espèces protégées

-

Réhausser les seuils pour les autorisations au regard des enjeux de souveraineté agricole et alimentaire

-

-

Renforcer la place des acteurs économiques dans la gouvernance des Comités de Bassin

-

Passer à 30 % le collège des représentants des usagers économiques de l’eau et des organisations professionnelles

-

Prédation

-

Octroyer à tous les agriculteurs la possibilité de défendre leurs troupeaux et leurs cultures face à tout prédateur et ravageur

-

Systématiser les dérogations L.411-2 contre les dégâts aux cultures ou troupeaux

-

Autoriser la chasse et l’effarouchement dans les parcs nationaux et réserves naturelles pour la défense des cultures et des élevages.

-

-

Autoriser le prélèvement des loups au-delà de 500 spécimens, sans condition de protection préalable ni limitation de durée

-

Poser le seuil de viabilité dans la loi à 500 loups

-

Autoriser un droit permanent de prélèvement au-delà de 500 loups, sans procédure ou condition préalable de protection ni limitation de durée

-

Permettre à tout éleveur de solliciter directement l’intervention des louvetiers

-

Autoriser la lunette de tirs à visée thermique aux éleveurs

-

Simplifier l’effarouchement des ours. Autoriser les tirs non létaux d’effarouchement dès la première attaque

-

Généraliser l’autorisation des autres moyens d’effarouchement sans condition préalable

-

-

Organiser la régulation des vautours par les Préfets du Département quand des comportements dommageables sont observés

-

Supprimer progressivement et interdire la création de placettes

-

Systématiser l’effarouchement et définir des seuils de population viables au regard des enjeux agricoles.

-

moyens de production

-

Améliorer les modalités de délivrance des AMM sur les produits phytosanitaires, les biocontrôles, les biocides et les produits vétérinaires et leurs exigences :

-

Principe de reconnaissance mutuelle systématique ;

-

Renversement de la charge de la preuve ;

-

Possibilité de complétude des dossiers en cours d’examen des demandes, prise en compte des nouvelles technologies, des conditions d’emplois similaires en Europe ;

-

Dérogation 120 jours sur des produits où l’homologation n’est plus demandée faute de marché suffisant ;

-

Prise en compte des nouvelles technologies

-

Des conditions d’emploi similaires en Europe

-

-

Développer les outils pour plus de prévention sanitaire

-

Etendre les missions du FMSE à la prévention

-

-

Limiter les atteintes à la production agricole dans les territoires

-

Limiter l’impact sur l’agriculture de la compensation écologique en instaurant un ordre de hiérarchisation de la compensation, en intégrant un principe d’additionnalité, en limitant l’application de la notion de proximité fonctionnelle et en encadrant les compensations surfaciques

-

Systématiser la compensation agricole

-

-

Réduire les charges liées à la protection des cultures

-

ZNT riverains :

-

Poser un principe de réciprocité et de compensation économique ;

-

Revenir sur les fondements législatifs des chartes riverains

-

-

Suppression de l’interdiction des 3 R

-

Suppression la RPD

-

-

Ne pas surtransposer et sur ajouter des règles en matière de bien-être animal

-

-

Ex des poules en cages

-

-

-

Lutter contre les intrusions dans les exploitations et des centres de recherche

-

Protéger les moyens de production (bâtiments et surfaces) par des sanctions pénales exemplaires

-

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

NDLR : le problème c’est que c’est pas une blague !

boissons chaudes,

boissons chaudes, crêpes sucrées,

crêpes sucrées,

fanfare

fanfare

et se tient toute la journée jusqu’à la clôture de l’audience en soirée.

et se tient toute la journée jusqu’à la clôture de l’audience en soirée. . Les 12 personnes seront amenées à faire leurs déclarations. Une série de témoins viendront à la barre apporter leurs expériences et leurs constats.

. Les 12 personnes seront amenées à faire leurs déclarations. Une série de témoins viendront à la barre apporter leurs expériences et leurs constats. Dans la salle, des scripts et des dessinateurs-trices feront une retranscription des échanges.

Dans la salle, des scripts et des dessinateurs-trices feront une retranscription des échanges.

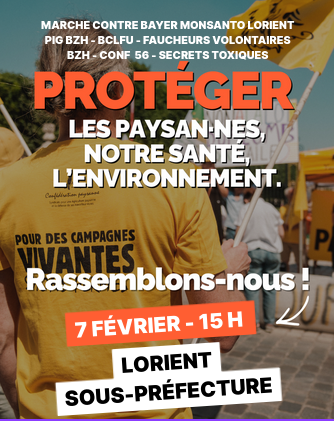

des points d’étape du procès, des prises de paroles, des témoignages. On vous accueille aux différents stands du village pour discuter, chanter, jouer, manger, se réchauffer et militer !

des points d’étape du procès, des prises de paroles, des témoignages. On vous accueille aux différents stands du village pour discuter, chanter, jouer, manger, se réchauffer et militer !

Préparez votre venue ! faite passer l’info, affiches et flyers disponibles sur

Préparez votre venue ! faite passer l’info, affiches et flyers disponibles sur